In thermodynamics, enthalpy is a measurement of the total energy of a system. It is specifically useful because it accounts for both the energy required to create the system (its internal energy) and the energy required to “make room” for it by pushing against the surrounding pressure.

The standard definition of enthalpy is the sum of the system’s internal energy plus the product of its pressure and volume:

H = U + PV

- H: Enthalpy (measured in BTU)

- U: Internal Energy (measured in BTU)

- P: Pressure (measured in lb/sq in or lb/sq ft)

- V: Volume (measured in cu ft)

Change in Enthalpy (ΔH)

In practical engineering and chemistry, we rarely care about the absolute enthalpy. Instead, we measure the change in enthalpy, which tells us how much heat was absorbed or released during a process at constant pressure.

ΔH = q

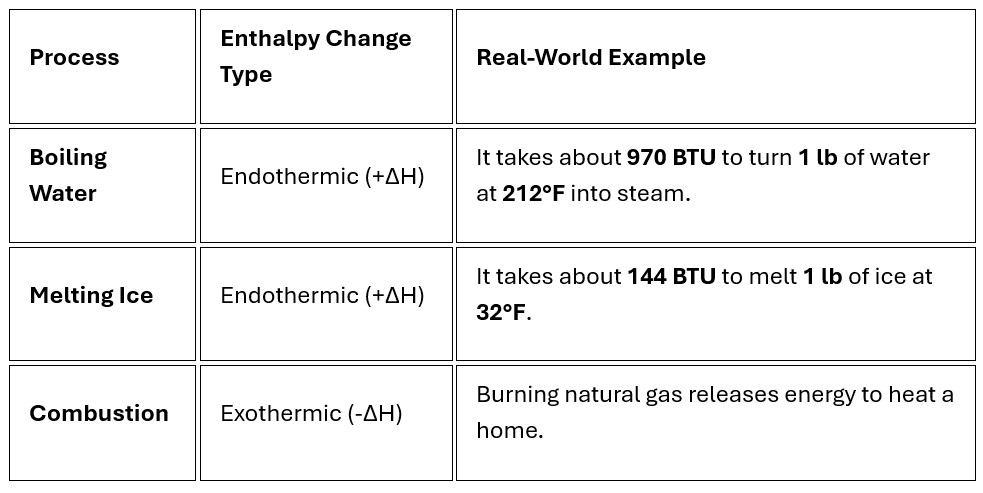

- Exothermic Reaction (-ΔH): The system releases heat to the surroundings (e.g., burning wood or freezing water).

- Endothermic Reaction (+ΔH): The system absorbs heat from the surroundings (e.g., melting ice or boiling water)

Why use Enthalpy instead of Internal Energy?

If you are heating a gas in a flexible container (like a piston), the gas expands as it gets hot. Some of the energy you add goes into moving the piston, not just raising the temperature. Enthalpy is a “shortcut” that tracks both the temperature rise and the expansion work at the same time, making it much easier to use for open systems like engines, turbines, and refrigerators.

Condensing & Evaporation

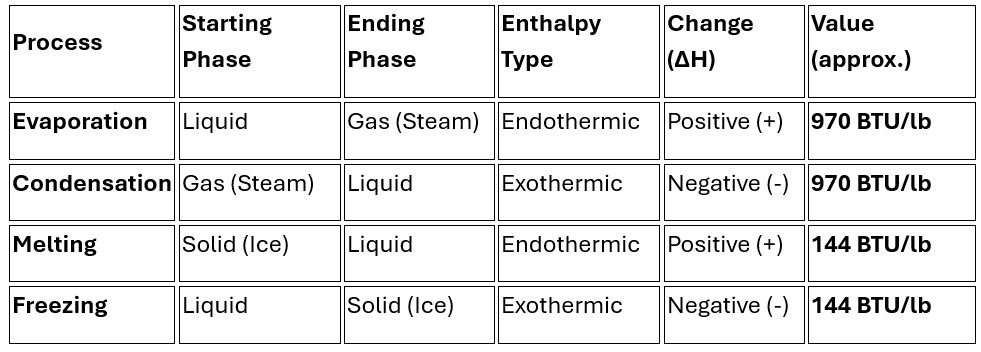

Many vacuum applications include condensing and evaporation during the process. In thermodynamics, the heat associated with these changes is called Latent Heat. Notice that evaporation and condensation use the same amount of energy per pound; the only difference is whether that energy is being added to the water or taken away from it.

Enthalpy Changes for Water Phase Transitions

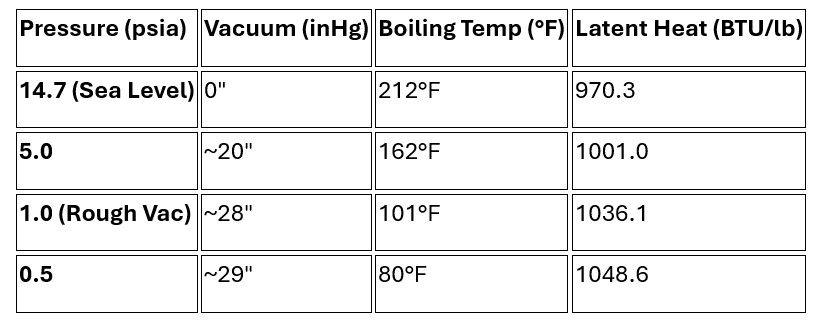

In a vacuum system, enthalpy and latent heat behave differently than they do at standard atmospheric pressure. As you lower the pressure (creating a vacuum), two major things happen: the boiling temperature drops, and the amount of energy required to evaporate the water increases.

- Latent Heat Increases in a Vacuum

It may seem counterintuitive, but it actually takes more energy to evaporate 1 lb of water in a vacuum than it does at sea level.

At atmospheric pressure (14.7 psia), the latent heat of vaporization is about 970 BTU/lb. In a rough vacuum (for example, at 1 psia), that value jumps to about 1,036 BTU/lb.

- Why? In a liquid, molecules are held together by internal bonds. At lower pressures and temperatures, the molecules have less “natural” kinetic energy, so you must add more external energy to break them apart and turn them into a gas.

- Enthalpy and Boiling Point

In a vacuum, the Saturation Temperature (boiling point) is much lower. This is the principle behind vacuum cooling and vacuum drying.

- Evaporation (The Cooling Effect)

In a vacuum system, evaporation is often used for cooling. Since the water “wants” to evaporate at a lower temperature, it will pull the necessary latent heat (~1,040 BTU/lb) from its own liquid mass or the surrounding equipment.

- This causes the remaining liquid to drop in temperature rapidly, a process known as Auto-refrigeration.

- Condensation in Vacuum

Condensation is the exact opposite. If you have water vapor in a vacuum line and it hits a cold trap or condenser, it must release that latent heat to turn back into a liquid.

- Because the latent heat is higher in a vacuum, your condenser actually has to work harder (remove more BTUs) to condense 1 lb of vapor than it would at atmospheric pressure.

If you are calculating heat loads for a vacuum system, you can use these general rules of thumb:

- Lower Pressure = Lower Boiling Point

- Lower Pressure = Higher Latent Heat (BTU/lb)

- Energy Released/Absorbed = Mass (lb) × Latent Heat (BTU/lb)